ADVANCEMENT PROJECT CALIFORNIA & THE NONPROFIT PARTNERSHIP

June 2021

ADVANCEMENT PROJECT CALIFORNIA & THE NONPROFIT PARTNERSHIP

June 2021

Central Long Beach

Executive Summary

Central Long Beach is an incredibly diverse area, though data sources do not accurately capture that diversity. Household incomes and unemployment, particularly among women and women with children, are below area medians. Families are rent-burdened, with Pacific Islander and Black households facing the most enormous financial strains due to rent. Many of these families live in the same areas defined by historic racist redlining efforts, showing the through-line connecting present racial disparities and past racial discrimination.

Residents of color are stopped most often for traffic violations, compared to all other racial groups in Central Long Beach. Surveys also reveal that whiter, wealthier residents in different neighborhoods of Long Beach are more likely to feel safe in their neighborhoods. In contrast, low-income residents of color feel harassed in their neighborhoods.

Pollutant sources in the greater Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach area have significant and disproportionate impacts on community air quality and health. Advocates find that their representatives are not accountable to their communities but instead to the industries working and polluting the Port. Asthma rates are high, and access to parks and healthy food is low.

These environmental and systems outcomes directly impact the health of and opportunities for young children and their families. Birth outcomes are racially disparate. Early childhood education (ECE) is crucial to child development, yet accessibility is a challenge for low-income residents. Third-grade test scores often found to be influenced by ECE access, are disparate, reflecting the ability of higher-income groups to find and pay for ECE. Further along in the K-12 years, suspensions and environmental conditions disproportionately push students of color out of schools. By extension, college readiness is low and unequal as well.

Each section of this report following Demographics (Education, Economic Wellness, Built Environment, Health, and Child Safety) identifies the gaps in Central Long Beach’s efforts to create an environment for families and children to thrive. First 5 LA Best Start, and the partners behind these efforts, are working to close these gaps. We humbly hope this report provides some baseline data and analysis in support of their advocacy.

The Central Long Beach area is a historic neighborhood within the City of Long Beach with just over 100,000 residents, including nearly 8,000 children ages 0-5. The area falls under City Council District 2, sharing borders with Wilmington, Signal Hill, and the Port of Long Beach. As a part of the County of Los Angeles, Central Long Beach falls under County Supervisorial District 4 and Service Planning Area (SPA) 8 (South Bay). Area children attend Long Beach Unified School District (LBUSD) schools.

Central Long Beach is a diverse community. Half of Central Long Beach residents are Latinx, while White and Asian residents are the second and third largest groups represented at 18.3 percent and 15.0 percent, respectively. Another 13 percent of residents identify as Black, and a smaller percentage represent Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (NHPI) and American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) populations. The lack of adequate data disaggregation is a disservice to the Asian community in Central Long Beach as the community itself is extremely diverse. The City of Long Beach holds the largest number of Cambodians outside of Cambodia and is also home to several other Southeast Asian groups.

Central Long Beach is Racially Diverse – Data Sources Don’t Account for the Diversity

Education is the foundation of development that unlocks potential for success. Early access to educational programs and resources before the age of five determine a child’s success in school and life. Early childhood education (ECE) programs provide access to trusted adults, social learning spaces, ensured meals, and arts and culture and safe, nurturing environments essential for promoting healthy development.

Early Childhood Education is Crucial to Development, Yet Accessibility is a Challenge

Subsidized ECE is available for infants, toddlers, and pre-Kindergarten (pre-K) children. However, there is a gap between eligibility and enrollment, largely due to lack of access, leaving large groups of young children without essential developmental supports. In 2018, nearly 24 percent of Central Long Beach children who were eligible for subsidized pre-K were not enrolled in a qualifying program. This percentage of unmet need is similar for infant toddlers (IT) who were eligible for subsidized ECE but not enrolled.

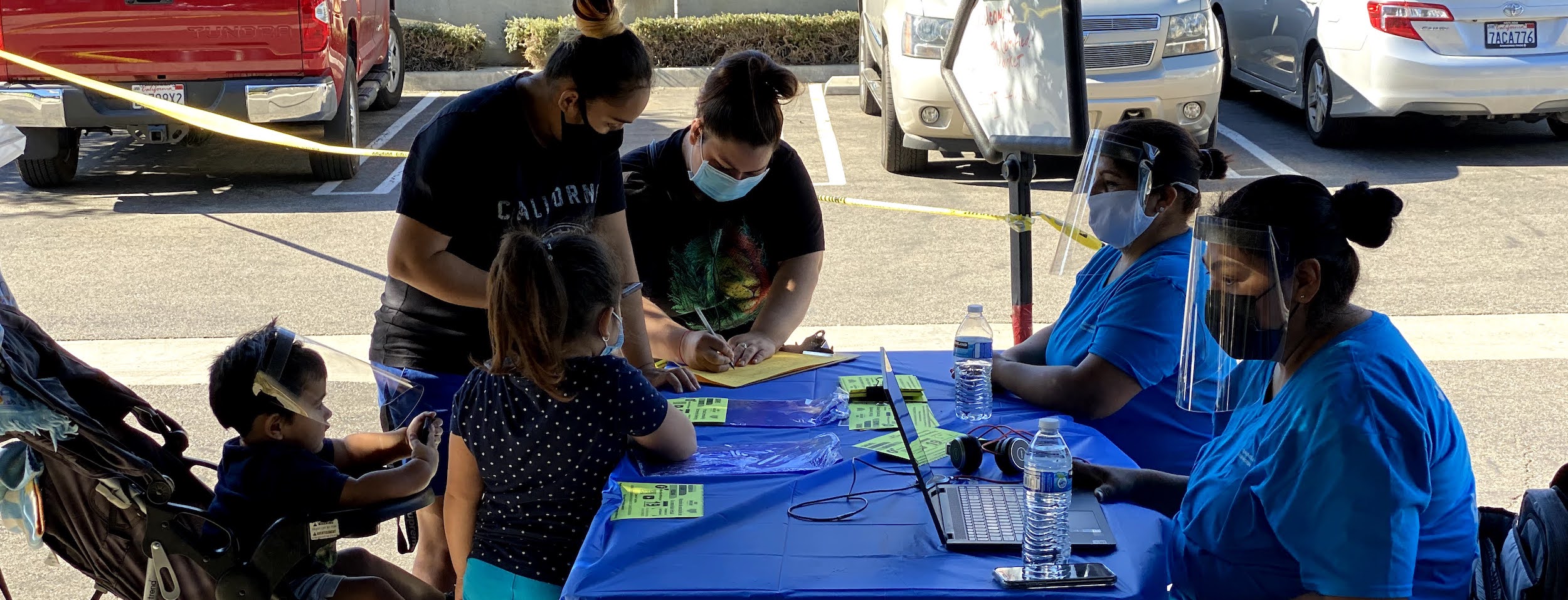

Several factors contribute to ECE inaccessibility. The lack of ECE facilities is one of the primary drivers, as supply of childcare facilities does not meet the demand. Insufficient state and federal funding, especially when compared to K-12 education funding, is another driver. Current ECE enrollment processes are burdensome on families, particularly for parents and guardians who are working. Most enrollment processes are manual and require parents or guardians to submit paperwork to multiple facilities in person. COVID-19 exacerbated the lack of access when working families dealt with closures of already competitive childcare sites, further highlighting the importance of ECE facilities. Investing in the livelihood of Central Long Beach’s future generations requires improving accessibility and increasing affordability to ECE among other strategies.

Children who begin kindergarten without access to ECE are already behind, and opportunity gaps are increasingly difficult to close as children grow older. Third-grade English and Math testing data is often used as a proxy to understand how ECE prepares children for K-12 education. The data for third-grade English and Math proficiency in LBUSD shows a low percentage of economically disadvantaged students are meeting the state standards. A total of 27.9 percent of economically disadvantaged third graders met state Math standards and only 23.8 percent met state English Language Arts standards in the 2019-20 school year. Focusing on economically disadvantaged students is an attempt to identify students more likely to reside in Central Long Beach, where median household incomes are lower on average compared to the rest of Long Beach.

While there is improvement to be made, LBUSD has better rates when compared to the larger and neighboring district, Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD). In LBUSD, 47.8 percent of economically disadvantaged third graders met or exceeded the standard for the CASSP English testing compared to 35.8 percent in LAUSD. For math, about 52.6 percent of economically disadvantaged third-graders met or exceeded the standard compared to 37.7 percent in LAUSD for the year 2018-2019. When looking at the racial disaggregation for this indicator, economically disadvantaged Black students are least likely to meet the proficiency levels for third grade testing in LAUSD but the rates are significantly higher for Black students in LBUSD (6.5 percent better for English and almost 10 percent better for Math). There are several reasons that could be driving the differences in testing outcomes for LBUSD and LAUSD students that are not explored in this report. Arguably one of the most notable differences is the sizes of the school districts, with LAUSD being the largest public school system in the state.

Community Spotlight: Long Beach Day Nursery

Long Beach Day Nursery is an early childcare provider in the South Bay that took care of over 300 students through its East and West branch locations prior to the pandemic. The overwhelming majority of children who attend Long Beach Day Nursery are children of essential workers who receive state support to access childcare. Children and families that attend Long Beach Day Nursery can receive wrap-around-services on site, including nutrition programs, early intervention programs, and mental health supports. “We try to get all the services that [parents and children] need on site,” says Long Beach Day Nursery Executive Director Jennifer Allen, who recognizes that working parents are not able to go to multiple locations for various services. As providers started reopening to limited capacity, Allen worked to prioritize children of essential workers to help ensure they received care while their parents continued to work. According to Allen, prior to the pandemic, ECE was not recognized as essential to those outside the industry. It took a global pandemic for everyone to quickly realize just how essential ECE is for young children and the labor economy.

Barriers to Education Disproportionately Impact Students of Color

Beyond early education, a student’s connectedness to school is another predictor of academic success. Community groups steering this report emphasized the importance of suspensions and expulsions that push students out of school. They also highlighted more passive activities that push out students, including lack of resources and support for chronically absent students or those facing homelessness. Without these services, conditions cannot exist for students to succeed.

Chronic absence plays a critical role in student achievement because of the lost learning opportunities. Schools with high or disparate rates of chronic absenteeism might fail to sufficiently engage families and communities. Language or cultural barriers, poor student-teacher relationships, and excessively punitive discipline policies reduce student connectedness. In LBUSD, 15.1 percent of students are chronically absent. The number one leading cause for chronic absenteeism is asthma which is unsurprising considering Long Beach’s historical issues with toxic pollutants in the air from the ports. Of the students who are chronically absent, AIAN students are 3.8 times more likely to miss a significant number of days at school compared to Filipinx students.

Another environmental issue that some students face in this district is homelessness. Students whose basic needs, such as housing, are not met face many barriers to strong academic performance. Among all students in LBUSD, 7.5 percent are experiencing homelessness, and more than half of homeless students are Latinx.

Unsurprisingly, students in racial groups who are more likely to be pushed out of classrooms are also less likely to be prepared for college. Latinx and Black students are part of the groups most likely to face student homelessness and chronic absenteeism, and schools in this community tend to prepare them for college at lower rates than the total student population.

There are several factors that can result in absenteeism, from health concerns to student homelessness or school suspensions, but they all result in the same consequence of children spending less time in the classroom learning. Systems should be working together to support student learning, especially those that have historically been pushed out at disproportionate rates. Black students are six times more likely to be suspended than their White peers. When students are out of school, they lose educational opportunities that define their future economic livelihood.

A family’s ability to provide the basics, including food, housing, transportation, health care, and an education, is directly related to their financial health. Children are vulnerable to the economic hardships their caretakers face and this may impede their path to achievement and success. Understanding the labor force, accessibility to economic opportunities, and rent burden bring light to some of the gaps Central Long Beach faces in fulfilling economic wellness for families in the area.

Female Head of Household are Least Likely to Participate in the Labor Force

Labor force participation is one indicator of a family’s access to employment and source of financial health. The data shows that single female heads of households are least likely to participate in the labor force in Central Long Beach. These households are also likely to be households of color. One national study found that 51 percent of Black children live with a single parent compared to 17 percent of White children.

Women already experience a pay gap compared to their male counterparts, and 2020 exacerbated the opportunity pay gap even more. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, women left the workforce at higher rates than men. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) compared rates in three different countries and found that, “Women with younger children have suffered larger job losses and/or drop-in hours worked than other women and men in all three countries. In the United States, for example, being a mother of at least one child under 12 years old reduced the likelihood of being employed by 3 percentage points compared to a man in a similar family situation between April and December 2020.”

Women of color experience both inequities – the pay gap and lack of employment opportunities – at worse rates than their white counterparts. As Central Long Beach plans for a just economic recovery post-pandemic, the data highlights a need to focus on women, specifically women of color. A lack of childcare spots makes it that much harder for households, especially single head of households, to pursue economic opportunities, making childcare accessibility a crucial part of recovery planning.

Two in Five Families Lack Broadband Internet Access

Broadband internet such as cable, fiber optic, or DSL allows access to relevant tools for economic and educational success. COVID-19 accelerated the already high demand for virtual communication via online video tools. In 2020, working and learning virtually became dependent on online video tools and broadband internet access. Almost overnight, the Southern California “stay-at-home” order left LBUSD to transition to distance learning. 60.3percent of families in Central Long Beach did not have access to Broadband Internet in 2019, which almost certainly means that students faced inequitable learning opportunities in 2020. LBUSD was one of the first and largest districts to begin a limited reopening at the end of March, but that reopening is also reported to benefit White children over children of color.

Families are Rent-Burdened, With Pacific Islander and Black Families Facing the Largest Financial Strain Due to Rent

Currently, more than half of the City of Long Beach residents are renters at 60.6 percent. In Central Long Beach, where median household incomes are significantly lower than in other parts of the city, families spend an even larger portion of their incomes on rent. This rent burden is disparate across races, with NHPI families spending more than one-third of their incomes on rent while White families on average spend 27 percent of their incomes on rent. On average, most families are spending over a quarter of their income on rent in Central Long Beach, but the number does not show the families on the higher and lower end of these spectrums. Families in Central Long Beach can have an average median household income at $30,000 at the low end and up to $60,000 at the higher end approximately. Federal policies indicate that spending more than 30% of your income on rent is considered being rent-burdened and is ultimately, a threat to family’s overall economic wellness. On average, Black and Pacific Islander families in Central Long Beach are spending more than 30% of their income on rent and the Latinx families show signs of being in danger of rent burden at 29.3 of their income spent on rent, on average. It is important to note that 30% of a larger share of income may not seem that burdensome but for families with on average lower median household incomes, like in Central Long Beach, 30% is not leaving families with the flexibility to spend on other essential needs.

Community Spotlight: Long Beach Residents Empowered and Long Beach Tenants Union

Housing advocates and families in the South Bay earned significant policy wins in tenant protections and inclusionary housing for their communities. During the height of the pandemic, Best Start members in Long Beach continued to face severe harassment from their landlords despite being protected from eviction through the state eviction moratorium. Landlords refused to make repairs in apartments, including addressing mold or rat infestations, and were spreading misinformation and fear among residents. They threatened to shut off power and evict them if they did not pay rent in full and on time. The new anti-tenant harassment ordinance passed in November 2020 bans landlords from these actions, with landlords in violation subject to $2,000-$5,000 in fines. It is through the tireless efforts of community organizers and families that this ordinance passed. They shared their stories and kept the pressure on the Long Beach City Council to push this policy through. In October 2020, Long Beach Residents Empowered and other advocates marched in Downtown Long Beach, denouncing the increased landlord harassment techniques. Several housing advocates, including the Long Beach Tenants Union, have also spoken repeatedly with news outlets to spread the word about the ordinance before its passing, to inform the public about the regulation and why it was essential.

The built environment refers to the physical space and infrastructure where a person lives and works, and it is an integral contributor to a child’s overall health. Central Long Beach is located next to two industrial ports and near industries creating high levels of air pollution, which lead to poorer health outcomes. These outcomes are directly connected to historic redlining policies. Redlining used race and environmental factors to determine the creditworthiness of different neighborhoods. It created artificial boundaries between “desirable” neighborhoods, where White families were allowed to obtain loans for housing, and less desirable neighborhoods, where people of color were allowed to obtain loans and mortgages. The majority of Central Long Beach was deemed too risky for investment by lenders and designated as hazardous, the lowest possible designation.6

In addition to redlining, local restrictive policies prevented Black, Asian American, and Latinx families from purchasing homes in predominately White neighborhoods.7 These racially driven policies institutionalized segregated neighborhoods, and people of color still experience the impacts of poorer environmental conditions today.

Neighboring Pollutant Sources Impact Air Quality and Health

The American Lung Association found that 9 of the 10 most ozone polluted metropolitan counties in the United States are in California, with Los Angeles County ranking third. Central Long Beach has many pollutant sources, including the ports, highways, and local industries. Research shows that pollution increases the risk for lung and heart diseases and can worsen asthma symptoms. Young children with asthma are specifically vulnerable to increased harm when exposed to high amounts of toxic pollutants.

Asthma emergency department visits per 10,000 people in Central Long Beach are ranked highest or high for every census tract in Central Long Beach when compared to the rest of California. The South Bay area is historically known for having some of the highest rates of asthma in all of Los Angeles County. There is a substantial amount of research that points to childhood asthma as a leading cause of chronic disease-related school absenteeism in the U.S., with more than 10 million missed school days annually. Additionally, the racial groups most likely to live in proximity to hazardous pollutant sources are people of color, driving the disparate educational outcomes that we know anecdotally and see in data results.

Black and Latinx populations in the City of Long Beach are more likely to live in areas where sensitive land uses, such as schools, playgrounds, health care, or childcare facilities, are within 1,000-3,000 ft. of hazards. The negative impacts from neighboring pollutant sources in Central Long Beach threaten the safety and health of children, particularly children of color.

Community Spotlight: Environmental Justice Work

Central Long Beach residents are uncomfortably familiar with the poor air quality caused by the proximity to pollutant sources. The “Fight Asthma Long Beach-Los Angeles Harbor” campaign, led by SmartAirLA and Long Beach Alliance for Children with Asthma (LBACA), works with grassroots community groups and policymakers to combat the hazardous pollutant sources harming the lives of South Bay residents. One of the impacts of living in proximity to environmentally dangerous sources is health impairments such as asthma. SmartAirLA and LBACA work with families who have asthma to make their voice heard by developing an active asthma danger map from community-identified sources. They provide a daily text message alert system for when the air quality is especially poor and dangerous for those with asthma to be outdoors. The campaign has created platforms and tools to call attention to the need for environmental and health equity. Learn more about their campaign and efforts at: https://fightasthmalaharbor.info/.

Central Long Beach, Along with the County, Struggles with Affordability and Access to Healthy Foods

Food issues in Central Long Beach include the ability to afford and access healthy food and the cultural and language capacities of food service providers. Currently, local racial disparities are difficult to measure in Central Long Beach because race data is only available in Los Angeles County and larger geographies.

Los Angeles County Health Survey (LACHS) reports a few different measures of food insecurity. Overall, households in the Long Beach health district reported slightly more food insecurity than the county overall, and Black and Latinx households were most likely to be food insecure.

Access to healthy foods is a separate but related issue. In SPA 8, White residents are most likely to be able to obtain affordable healthy foods and AIAN residents least likely.

Forthcoming research from the Los Angeles Food Policy Council details community concerns within Central Long Beach. In surveys, community members expressed the following as their top concerns: access to services, cultural and linguistic capacity, and accessibility. Community members expressed confusion over different governmental programs, eligibility standards, and documentation requirements. In addition, language access was critical as several community members expressed a belief that non-English speakers were at a disadvantage. Many also found it hard to travel out of the community to receive services and reported that service sites were not family-friendly.

Community Spotlight: Food Accessibility during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond

The Long Beach community has stepped up in heroic ways to support one another during the worsening food accessibility crises. Families who experienced job loss during the pandemic and the resulting financial strain are having a difficult time obtaining food. In response, churches are hosting food distributions, neighbors are delivering meals to each other, and pop–up food delivery services are ensuring that there is more food to go around. The City of Long Beach Health and Human Services also approved funding to go to 16 nonprofit organizations to support food distribution efforts which lasted through March 2021. While the social benefits of a strong-knit community that looks after one another are incalculable, the fact remains that food inaccessibility is a systemic problem. The grassroots effort to increase food access highlights the strength and compassion of the community, but also highlights where system players are failing. Government bodies and larger systems of power should ensure that community members have sustainable access to healthy and affordable food. Real food security in Long Beach looks like more healthy and affordable food options, as well as farmers markets that are located throughout the community, making them easily accessible to everyone, especially higher need families. Food access also looks like families having steady incomes and job stability that allows them to be able to afford food and not rely on distribution centers and food pantries.

Socioeconomic and environmental factors contribute to the health of families and children. Disparate health outcomes for children and mothers are largely driven by the systemic inequities that make it harder for women of color to access timely and quality health care. Preventative health is the best way to avoid dangerous and costly health problems later in life but is impossible without an environment that is conducive to healthy living.

Birth Outcomes are Racially Disparate; Best Start is Working to Change That

Most census tracts within the Central Long Beach area fall in the bottom quintile of the Children’s Data Network’s Strong Start Index, highlighting some of the health care access issues that negatively impact mothers and children. The index is based on twelve indicators including healthy birthweight, access to and receipt of timely prenatal care, and the ability to afford health care.

The Children’s Data Network also calculated infant mortality rates. In Central Long Beach, the average infant mortality rate of 3.3 per 1,000 live births is slightly below the Los Angeles County rate of 3.6 per 1,000 live births. Countywide, infant mortality rates are higher for low-income, Black, and U.S.-born Latinx families. This disturbing racial disparity holds true in the Long Beach area as well. Long Beach Health and Human Services Department reports a higher infant mortality rate of 4.2 per 1,000 live births. It also shows far higher infant mortality rates for Black families than for families of other races. Numerically, more than half of Long Beach infant deaths between 2013 and 2017 were to Latinx families.

At the core of a child’s ability to thrive is their ability to feel safe. A sense of safety contributes to a child’s social and emotional development and impacts health outcomes. Children who are consistently exposed to unsafe conditions, such as accumulated burdens of family economic hardship, violence, or abuse, are at risk of stress-related diseases and cognitive impairment later in life. Police harassment is one area partners identify as working against safety.

Neighborhood Safety linked to Race in Los Angeles County and Central Long Beach

The RACE COUNTS – PUSH LA report, Reimagining Traffic Safety & Bold Political Leadership in Los Angeles, makes clear that stops and arrests are racially and economically biased, costly for communities, and an inefficient means of advancing traffic safety. An analysis of related data shows that traffic stops and arrests in the Long Beach area are not materially different.

Black, NHPI, and multiracial drivers in Long Beach were stopped at higher rates than White drivers, according to data collected from the Long Beach Police Department. Black drivers were stopped at a rate of 195 times per 1000 people, while White drivers are stopped 71.7 times per 1000 people.

Perceptions of safety are a nuanced issue in Central Long Beach. In surveys, Central Long Beach residents (as a part of larger survey geographies) are as likely or more likely to feel safe in their neighborhoods than others in the city and county, though residents of color are less likely to feel safe than Whites. However, when safety in parks is assessed, Central Long Beach residents are less likely to have access to parks, playgrounds, or other safe places to play than other communities in the County.

LACHS reports that an overwhelming majority of adults in the Long Beach health district, approximately 99.4 percent, were likely to perceive their neighborhood as safe from crime compared to 85 percent of adults in the county who perceive their neighborhood as safe from crime. While health district racial breakdowns are not available, countywide White adults were more likely to perceive their neighborhoods as safe than were Latinx adults. Data in SPA 8 on the other hand show that adults felt as safe as county adults, though still with significant differences by race. 92.5 percent of non-Hispanic White adults reported feeling safe in their neighborhoods compared to 76.2 percent of Latinx adults and 58.3 Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander adults.

Access to safe parks or places to play is a different story. Countywide, caregiver respondents told the LACHS that 90.4 percent of children ages 1-17 have easy access to a park, playground, or other safe place to play. A First 5 LA analysis of LA County Department of Parks and Recreation data had a similar result with 91.1 percent of children 0-5 living within one half-mile of a park or open space. On the other hand, those in the Long Beach health district on the other hand reported lower access, with only 82.8 percent of Long Beach children reporting easy access.

Central Long Beach is a diverse community with incredible organizations, individuals, and families striving to build a place of opportunity for the next generation. Racial disparities in outcomes and systems not yet attuned to addressing them stand in the way. While the data presented does not present the complete picture, it introduces some of the issues facing families in Central Long Beach, such as the need for investment in early childhood education and reducing hazardous pollution sources. Each highlighted issue plays a vital role in supporting that a child must have to live a prosperous and healthy life.

We are hopeful this report helps community partners advocate for change to the systems currently falling short. We are inspired by the organizations, including those in the Community Spotlights, to make those changes happen. We thank the contributors to this report, and we look forward to future iterations that are co-created or wholly created by partners. To learn more about the data used in this report and future iterations, please find the interactive visuals on [insert link to site] and read about the report on the neighboring community of Wilmington, please click here, [link to Wilmington report].

1. City of Long Beach, “Timeline of Racial Inequities in Long Beach,” 2020, https://longbeach.gov/health/healthy-living/office-of-equity/reconciliation/equity-timeline/.

2. McCoy DC, Yoshikawa H, Ziol-Guest KM, Duncan GJ, Schindler HS, Magnuson K, Yang R, Koepp A, Shonkoff JP. Impacts of Early Childhood Education on Medium- and Long-Term Educational Outcomes. Educ Res. 2017 Nov;46(8):474-487. doi: 10.3102/0013189X17737739. Epub 2017 Nov 15. PMID: 30147124; PMCID: PMC6107077.

3. “Why Is Early Childhood Education Important?,” National University, November 13, 2020, https://www.nu.edu/resources/why-is-early-childhood-education-important/.

4. American Institute for Research, “Early Learning Needs Assessment Tool,” 2018. https://elneedsassessment.org/.

5. McCoy DC, Yoshikawa H, Ziol-Guest KM, Duncan GJ, Schindler HS, Magnuson K, Yang R, Koepp A, Shonkoff JP. Impacts of Early Childhood Education on Medium- and Long-Term Educational Outcomes. Educ Res. 2017 Nov;46(8):474-487. doi: 10.3102/0013189X17737739. Epub 2017 Nov 15. PMID: 30147124; PMCID: PMC6107077.

6. California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress, “Test Results at a Glance”, 2019-2020. https://caaspp-elpac.cde.ca.gov/caaspp/DashViewReport?ps=true&lstTestYear=2019&lstTestType=B&lstGroup=3&lstSubGroup=31&lstGrade=3&lstSchoolType=A&lstCounty=19&lstDistrict=64725&lstSchool=0000000&lstFocus=a

7. California Department of Education, “Largest & Smallest Public School Districts – CalEd,” 2019-2020. Largest & Smallest Public School Districts – CalEd – Accessing Educational Data (CA Dept of Education)

8. Mortimer et al., “Parental Economic Hardship and Children’s Achievement Orientations,” 2014, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4358300/.

9. Gretchen Livingston, “About one-third of U.S. children are living with an unmarried parent,“ Pew Research Center, April 27, 2018, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/27/about-one-third-of-u-s-children-are-living-with-an-unmarried-parent.

10. Alissa Anderson, “California’s Recent Job Gains Are Promising, but Policy Choices Now Will Determine if an Equitable Economy Is Ahead,” California Budget and Policy Center 2021, https://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/californias-recent-job-gains-are-promising-but-policy-choices-now-will-determine-if-an-equitable-economy-is-ahead/.

11. Georgieva et al., “COVID-19: The Mom’s Emergency”, April 30, 2021,

https://blogs.imf.org/2021/04/30/covid-19-the-moms-emergency-2/.

12. Payscale, “The State of the Gender Pay Gap in 2021,” March 24, 2021, https://www.payscale.com/data/gender-pay-gap.

Economic Policy Institute, “Black workers face two of the most lethal preexisting conditions for coronavirus–…,” June 1, 2020, https://www.epi.org/publication/black-workers-covid/.

13. Guardabascio and Dobrucj, “Which LBUSD families will send back to class?…,” March 9, 2021, https://lbpost.com/news/education/whos-going-back-school-rich-white-lbusd.

14. US Census Bureau, ”Quick Facts Long Beach City, California”, July 1, 2019. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Long Beach city, California

15. U.S. Census Bureau; American Community Survey, 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table S1101; generated by Maria Khan; using data.census.gov; https://data.census.gov/cedsci/.

16. Schwartz & Wilson, US Census Bureau, “Who Can Afford to Live in a Home?” Accessed June 2021. https://www.census.gov/housing/census/publications/who-can-afford.pdf

17. Schwartz & Wilson, US Census Bureau, “Who Can Afford to Live in a Home?” Accessed June 2021. https://www.census.gov/housing/census/publications/who-can-afford.pdf

18. City of Long Beach, “Ordinance No.20-0044.” November 11, 2020. https://www.longbeach.gov/globalassets/city-clerk/media-library/documents/public-notices/ordinances/ord-20-0044–emerg

19. American Lung Association, “Most Polluted Places to Live,” April 20, 2021, https://www.lung.org/research/sota/key-findings/most-polluted-places.

20. Long Beach Department of Health and Human Services, “Community Health Assessment,” 2019, https://www.longbeach.gov/globalassets/health/media-library/documents/healthy-living/community/community-health-assesment.

21. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, “Asthma-Related School Absenteeism, Morbidity, and Modifiable Factors,” February 9, 2016, https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(15)00792-8/fulltext.

22. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health Survey. 2018. Distributed by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/ha/docs/2018LACHS/MDT/Adult/M3_SocialDeterminantsOfHealth/M3_FoodInsecurity_FDSECOA.xlsx.

23. Los Angeles Food Policy Council, “Food Equity and Access”, 2018. Food Equity and Access — Los Angeles Food Policy Council (goodfoodla.org)

24. First 5 LA, “Indicators of Young Child Well-Being in LA County,” 2020, https://www.first5la.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/First-5-LA-2020-Indicators-Report.pdf.

25. Long Beach Health and Human Services, ”Infant & Maternal Health,” 2021, https://dashboards.mysidewalk.com/long-beach-cha/infant-maternal-health.

26. St. Mary Medical Center, ”Community Health Needs Assessment,” May 2019, https://www.dignityhealth.org/socal/-/media/Service%20Areas/socal/PDFs/SMMC-LB%202019%20CHNA.ashx.

27. Toxic Stress,” Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, August 17, 2020, https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/toxic-stress/#:~:text=Toxic%20stress%20response%20can%20occur,hardship%E2%80%94without%20adequate%20adult%20support.

28. Advancement Project CA, ”Reimagining Traffic Safety & Bold Political Leadership in Los Angeles,” 2021, https://www.racecounts.org/push-la/.

29. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health Survey. 2018. Distributed by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/ha/docs/2018LACHS/MDT/Adult/M7_SpecialTopics/M7_NeighborhoodSafety_NSH.xlsx.

30. UCLA Center for Health Policy and Research, Los Angeles, CA. AskCHIS 2011-2018. How often fresh fruits/vegetables affordable in neighborhood (Los Angeles, SPA 8). Available at http://ask.chis.ucla.edu